Autosomal Dominant spinocerebellar ataxia - case presentation .

Case Description

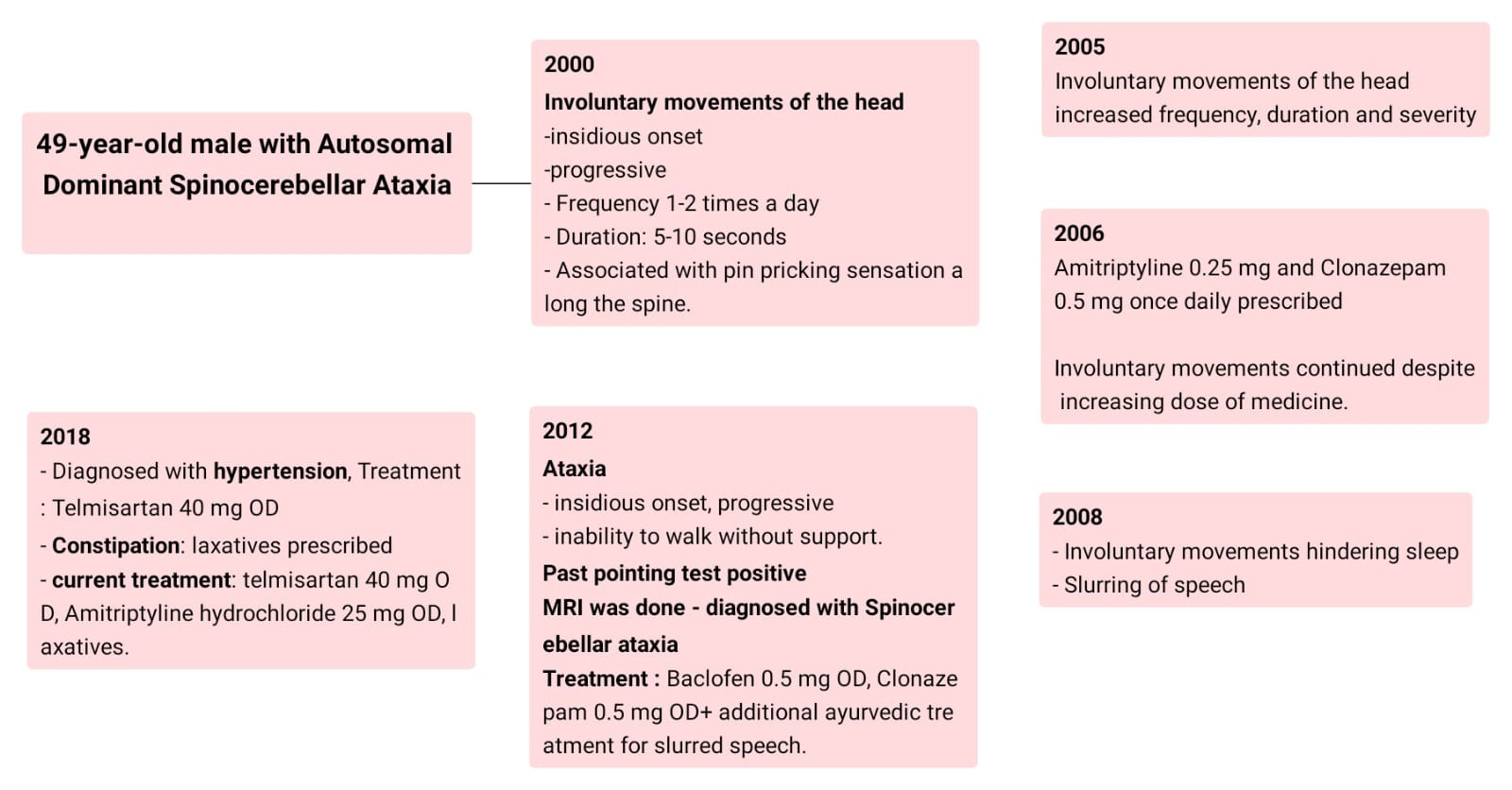

A 49-year-old male, with a history of hypertension, a businessman by occupation, presented with involuntary movements of the head.

The patient was apparently asymptomatic till the year 2000, while

watching television, he felt the back of the neck and head become stiff, and soon after,

he experienced involuntary movements of his head, moving from

side to side (The patient described It as if he was saying no with the movement

of his head alone). They were insidious in onset and progressive in nature. Initially, the involuntary movements were visible only on careful observation. It lasted 5 to 10 seconds and happened 1-2 times a day, a few times a week. The involuntary

movements of the head were associated with a pin-pricking sensation

along his spine.

By the year 2005, the involuntary movements of the head

increased in frequency, duration and severity such that the patient was unable to

complete the task at hand. At this point, the patient visited a local physician

but the medications did not provide relief.

In 2006, the patient visited a higher centre, where the

doctor prescribed Amitriptyline 0.25 mg and Clonazepam 0.5 mg once daily. These

medications provided some relief for 3 months. After this the involuntary

movements continued even after increasing the doses of medicines. The patient also tried homoeopathic medication,

but it did not provide any relief.

In 2008, the patient started experiencing reduced sleep,

whenever he tried to rest, in the the supine position, the involuntary movements of the

head reappeared, thus he had to lie down on his sides. The patient also started

experiencing slurring of speech.

By the year 2012, the patient developed ataxia which

was insidious in onset and progressive in nature. In a year, the patient was unable

to walk without support. past pointing test was positive. He visited a

doctor where an MRI was done and the patient was diagnosed with Autosomal

Dominant Spinocerebellar degeneration. The patient was treated with Baclofen 5mg

and clonazepam 0.5 mg. The patient experienced some relief from symptoms for a

few months. He also started ayurvedic treatment, which was found beneficial, for

slurred speech -which included chewing the roots of the plant piper longum. The

patient stopped taking medication as it was not providing any relief.

In 2018 the patient was diagnosed with hypertension and was

started on telmisartan 40 mg Once Daily. The patient also complained of

constipation and consumes laxatives occasionally. The patient was started on

Amitriptyline Hydrochloride 25 mg OD for symptomatic management.

There is no history of muscle weakness, abnormal eye movements,

dysarthria, loss of sensations, or visual or hearing impairment.

There are no features of parkinsonism, epileptic seizures, or myoclonus.

The current treatment includes Amitriptyline Hydrochloride

25 mg OD, telmisartan 40 mg OD and physiotherapy.

Family History

![]()

Father: No known medical issue. Died

in 2003.

Mother: diagnosed with Autosomal

dominant Spinocerebellar degeneration at the age of 34 and passed away at the

age of 35

Elder sister: Died in 2003 due to

autosomal dominant spinocerebellar ataxia at the age of 41

Elder brother: diagnosed with

Autosomal dominant Spinocerebellar degeneration in 2003, died: in 2013 at the age of

42

Younger sister: Died: in 2021 due to

autosomal dominant spinocerebellar ataxia at the age of 56

Wife: No medical issues

Daughter: No symptoms of disease till

now.

Case discussion:

This case depicts the clinical progression of the disease.

Autosomal

dominant spinocerebellar ataxias are progressive in nature characterised by slow

degeneration of the cerebellum accompanied by degeneration of other parts of

the central nervous system including the brainstem. [1]

A

patient is known to have a genetic form of ataxia when there is

-

History of

insidious onset

-

Slow

progression

-

Bilaterally

symmetrical findings on examination

-

Positive family

history of ataxia in the patient’s parents. 1

In our patient,

the patient’s mother was diagnosed with Autosomal Dominant Spinocerebellar Ataxia.

and the history of ataxia is consistent with the above findings.

The global prevalence of spinocerebellar ataxia is noted as

3 in 100,000 [3]

Though prevalence studies in all countries note idiopathic

cases of Spinocerebellar degeneration. Median Proportions of Patients with

Spinocerebellar degenerations with unknown aetiologies include 38.5 per cent in

India. While SCA2 is the most common subtype prevalent in India [2]

A study to find the severity and survival in

Inherited spinocerebellar ataxias found that survival was 68 years in 223

patients with polyglutamine expansions, versus 80 years in 23 patients

with other mutations. Disability was also more severe in patients with

polyglutamine expansions.[4]

Clinical Features

All patients with this disease present with cerebellar ataxia,

but the additional symptoms are variable. [5]

For Instance, according to the gene involved – [1]

|

Involved gene |

Clinical

features |

|

SCA1 |

signs of widespread cerebellar and brainstem

dysfunction with relatively little supratentorial involvement. |

|

SCA2 |

ataxia, dysarthria, slow saccades, and peripheral

neuropathy |

|

SCA3 |

progressive ataxia, lid retraction,

infrequent blinking, ophthalmoparesis, impaired speech and swallowing |

|

SCA5 |

a relatively pure form of slowly progressive dominant cerebellar

ataxia |

|

SCA6 |

pure” cerebellar ataxia accompanied by

dysarthria and gaze-evoked nystagmus with onset at 20 years. |

|

SCA7 |

the universal presence of retinal degeneration with ataxia |

|

SCA8 |

Prominent gait and limb ataxia, abnormalities of swallowing,

speech and eye movements |

|

SCA10 |

prominent cerebellar symptoms and

seizures. |

|

SCA11 |

pure” cerebellar syndrome with mild pyramidal signs slowly progressive form of gait and limb ataxia |

SCA12

|

more common in India Age at onset ranges between 8 to 60 years first symptom typically being an action tremor of the arms.

The tremor is eventually accompanied by head tremor, ataxia, and sometimes

bradykinesia and sensory neuropathy. |

SCA13

|

widely varying ages of onset Common features are ataxia, dysarthria, nystagmus, and occasionally

hyperreflexia. |

SCA14

|

slowly progressive ataxia with dysarthria in early adulthood In late-onset cases, SCA14 can manifest as a relatively pure

cerebellar ataxia |

SCA15/16

|

slowly progressive, pure cerebellar ataxia Dysarthria, horizontal gaze-evoked nystagmus, and impaired

smooth movement of the eyes are present in some patients. Approximatelyone-thirdd of patients have a head tremor. The disease is caused by small genomic

deletions encompassing the IPTR |

SCA17

|

young-adulthood or mid-adulthood progressive gait and limb ataxia dementia, psychiatric symptoms, and varying

extrapyramidal features, including parkinsonism, tremor, dystonia, and

sometimes chorea, seizures |

SCA20

|

initial symptom is

dysarthria rather than gait ataxia, accompanied by palatal tremor,

hypermetric saccades, and dentate calcification in the cerebellum |

SCA27

|

early-onset ataxia manifest first

with handtremorsr in childhood followed by progressive ataxia, cognitive

difficulties, and psychiatric problems in the second and third decades of

life. |

According to the following findings, the clinical features

in our patient are most consistent with SCA12.

MRI and genetic testing in addition to a through family

history are usually done in order to diagnose a patient with Autosomal Dominant

Spinocerebellar ataxia. On the MRI for diagnosis there should be presence of

cerebellar atrophy and evidence of structural or vascular damage and or other

lesions or associated neurodegeneration. [5] Our patient underwent MRI in the

year 2012, and was diagnosed with Inherited Spinocerebellar ataxia, but due to

lack of documentation, the patient lost the reports.

Genetic testing can be done in 5 distinct scenarios – diagnostic testing,

predictive testing, prenatal testing carrier testing, and risk factor assessment. In reality, however, only

diagnostic and predictive testing concern the practicing physicians. [1]

On the basis of genetic testing various SCA genes are identified, and

clinical features are noted as depicted in the table above. However, in our

patient the genetic testing was not done.

There is presence of very strong family history in our patient

consistent with autosomal dominant spinocerebellar ataxia.

There is no effective treatment for

genetic and idiopathic ataxia, hence includes symptomatic treatment an exercise

therapy to maintain patient function. [5]

This was incorporated in the management

of our patient as well.

Learning Outcomes

The following consultation occurred as telecommunication, A

PAJR group was created. This group aimed at understanding the patient’s

problems and providing the best possible solution in terms of pharmacotherapy

and exercise therapy. In addition to this the patient also found a way to describe

his day-to-day activities which added to the accountability of the patient to

maintain a healthy diet, compliance with exercise and pharmacotherapy was

checked on a daily basis.

SWOT analysis of this approach is as follows.

Strength:

-

The patient found a means of communication, to

express his difficulties on a day-to-day basis, these were immediately managed.

-

The group provided a way to determine the family

history which was very essential in the diagnosis.

-

The PaJR group acted as a means of compliance in

terms of exercise and pharmacotherapy.

Weakness

-

There was lack of face-to-face communication and

a lack of human touch acted as a major drawback especially in a disease wherein,

the prognosis is not good.

-

Language barrier: As the patient speaks a

different language than most doctors on the PaJR group, it hindered in

immediate management.

-

Lack of investigations and lost reports were a

major drawback.

Opportunities:

-

This approach allowed a detailed history and an

understanding of how the disease affected the individual in terms of day-to-day

activities

-

It acted as a platform for medical students to

directly see how a patient would present with this disease

-

It also acted as a platform for doctors to

discuss treatment and research modalities.

Threats:

-

Inability for members of the group to understand

the patient’s problems due to a language barrier.

References

1.

Paulson,

H. L. (2009). The spinocerebellar ataxias. Journal of

Neuro-Ophthalmology: The Official Journal of the North American

Neuro-Ophthalmology Society, 29(3), 227–237. https://doi.org/10.1097/WNO0b013e3181b416de

2.

van

Prooije, T., Ibrahim, N. M., Azmin, S., & van de Warrenburg, B. (2021).

Spinocerebellar ataxias in Asia: Prevalence, phenotypes and management. Parkinsonism

& Related Disorders, 92, 112–118.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.parkreldis.2021.10.023

3.

Luis RuanoClaudia MeloM. Carolina SilvaPaula Coutinho; The Global Epidemiology of

Hereditary Ataxia and Spastic Paraplegia: A Systematic Review of Prevalence

Studies. Neuroepidemiology 1

April 2014; 42 (3): 174–183. https://doi.org/10.1159/000358801

4.

Monin, L., Marelli, C., Cazeneuve, C., Charles,

P., Tallaksen, C., Forlani, S., Stevanin, G., Brice, A., & Durr, A. (2015).

Survival and severity in dominant cerebellar ataxias. Annals of Clinical and

Translational Neurology, 2(2), 202-207. https://doi.org/10.1002/acn3.156

5.

Shakkottai, V. G., & Fogel, B. L. (2013).

Autosomal Dominant Spinocerebellar Ataxia. Neurologic clinics, 31(4).

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ncl.2013.04.006

6. Link to first case report - https://ssahamedicalcases.blogspot.com/2023/02/patient-history-pt-is-49-yrs-old-male.html?m=1

|

|||

|

|||

Comments

Post a Comment